-

Lessons From My Graduate Year in the Netherlands as a non-EU: A Reflection on Resilience

Resilience can form in the strangest places. It has blistered over the troubled spirits of men in the wilderness, illuminated minds in the darkest of caverns, and rooted itself in well-worn hearts beneath the cooling shade of trees. Across the heady halls of history the character-defining discrimen of resilience has touched thousands in scenes befitting its reception.

Would that I could be so lucky — when resilience found me I was on my knees scraping shit off a toilet seat.

These were the dying days of December and winter in the Netherlands had advanced in its steady-step of mottled greys and cast out whites, bringing with it a cold conclusion to a year that had nearly sucked the spirit out of me. It wasn’t just the incessant nip of a Dutch winter that made it exceptionally cold, but the bitterness of what I had learned to accept throughout the year. Death, deception, heartbreak and hardship. These weren’t the angsty tracks of a bad punk album, but self-standing stories in a film that had flashed across 2024, the last of which had culminated during Christmas. It was in that toilet, during my late night Christmas shift as I blinked past tears while scraping someone else’s shit off the toilet seat for minimum wage and weighed the turbid unknowns of my future — that resilience found me.

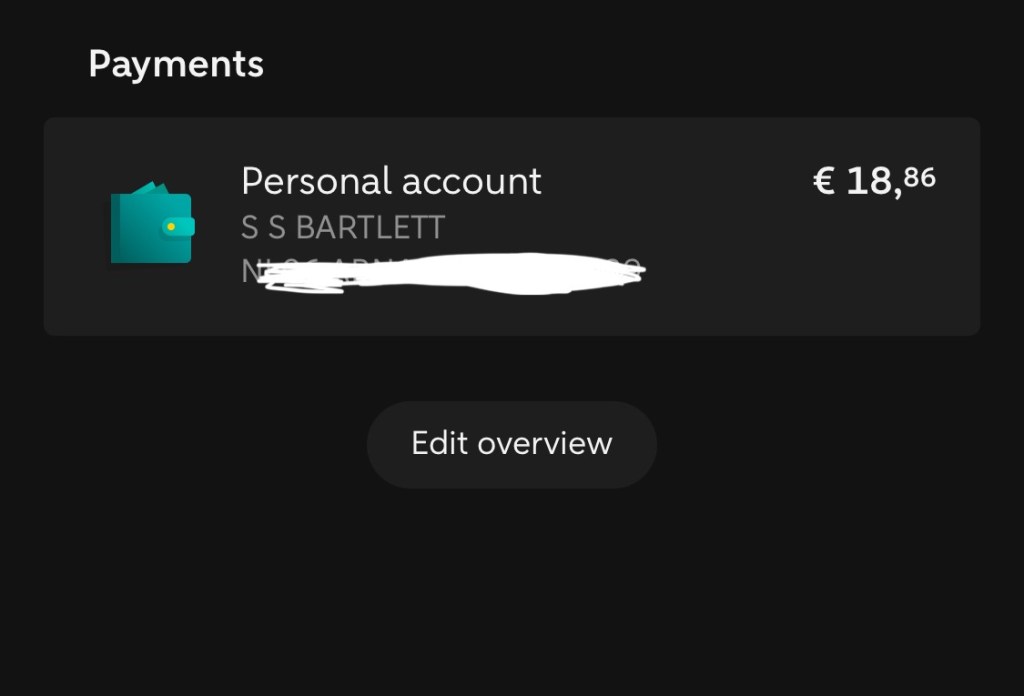

When I graduated from an MSc in International Development Studies from Wageningen University, I asked what any graduate asks,“alright universe, what do you have in store for me?”. The universe abhors many things, but above all it abhors a cliché and decided to answer my lack of originality with a sucker punch where it hurt — my wallet. To face the world and what it had in store, I found myself post-graduation with a degree in one hand and exactly 18 euros and eighty-six cents in the other. A combination of Sri Lankan capital controls, exorbitant non-EU fees, and added visa expenses for my graduate visa had decided that henceforth my meals would be rice and lentils. Rice and lentils. Rice and lentils. Rinse. Cook. Repeat.

A screenshot as a memory in a moment of frustration I searched for work like children search for Pokémon cards. I was a janitor moonlighting as a waiter moonlighting as a cook moonlighting as a factory worker moonlighting as a photographer. Add that to your AI-generated LinkedIn bio. My days began at 4:30AM, sometimes sooner. On others they ended at 4:30AM, sometimes later. Too often one shift ended, just for a few hours of sleep before the next shift began. Working to live can make for a deadly concoction, but there are things you need to get done, so you can survive to do the things you’re meant to do.

Many of my friends and classmates graduated and left Wageningen for globetrotting holidays and job opportunities; it wasn’t long before routine, rumination and the cold caress of an early hour bike ride to or from work were my sole company. In between shifts as I tried to grab bursts of sleep, housemates who partied from Friday night deep into Saturday morning, would try to invite me to their gatherings saying “hey man, all we see you do is go for work, want to join?” — but joining isn’t an option when you have to set yourself apart.

It’s easy to feel sorry for yourself when the whole world seems to be leaving you behind while you scrape the bottom of your bank account to wonder which groceries you can forego this month so you can afford to live the next month — you bet my bottom eighteen-euros I did. But above feeling sorry for myself a quiet rage and defiance had been building in me and with it came a need to outperform and outclass my peers. This was survival. Competition. Jealousy. Each at its worst. I do not recommend it. All that hate’s gonna burn you up, kid.

Driven by instinct, and haunted by the lack of prospects in my future, I woke up each day before my shifts, carving out an hour of my already scarce sleep so that I could find an hour to tailor make a CV or cover letter. There were times when the nights had blurred into mornings that I tasted tears, and some nights that I tasted nothing at all and went to sleep hungry — But through it all I was so angry. At the system. At my luck. At my own naivety to think that having two masters degrees and non-EU international experience would at least get me an interview in the Netherlands.

Ultimately, it was my body that caved before my mind. One night, not long after I had fallen asleep sucking up the end of my then relationship, I woke up to the stabbing sensation of knives in my palms. My fingers were so paralysed with pain, I could barely feel them flick on the light. Repeated movements as a factory worker, janitor, waiter and what-had-you had come at a cost. Both my hands had developed acute carpal tunnel syndrome.

To this day I don’t know if the managers at my job believed me when I reported-in sick for work, but if they could read this now it might occur to them that it was truly a break I couldn’t afford to have. I was in all aspects running on empty. The doctor, a middle-aged man with a face just as pragmatic as his tone, gave me two options. “You can either stop working or you can be referred for surgery.” He said, with the hint of a smile that I couldn’t tell was amusement or pity.

Options are a luxury when you’re trying to survive. My only recourse was to continue working, but to work slower. Sleep more and sign up for one-to-two fewer shifts. My hands continued to burn numb each time, and if anyone saw me in the factory they might have seen me treat my arms with all the due respect of two dead stumps as I lifted block after block of product into an orifice of conveyor belts and machinery. All however, was not lost. When the first pay cheques cashed into my account, eighteen euros became hundreds, and hundreds became a thousand. Soon, I had divided my money into savings for future emergencies, and my monthly upkeep. Life was far from cosy, but I could finally afford to rest a little longer. I could afford to complement my rice and lentils with something nicer like tuna or greens. Fancy.

By this point my mind was as numb to the routine as my body. Even on my rare off-days my body would wake me up automatically (if my hands didn’t startle me awake) and I would spend that time typing out job applications in the predawn dark. But now I was less hungry. Less angry and more appreciative. As painful as it was, all I had learned and felt and seen suddenly seemed like sharp lessons that had been etched into my perception of how I would forever understand hardship — how I would respond to times of uncertainty and how I would adapt. It didn’t dawn on me then, but I think the appreciation of what suffering teaches you is the first step in your emancipation.

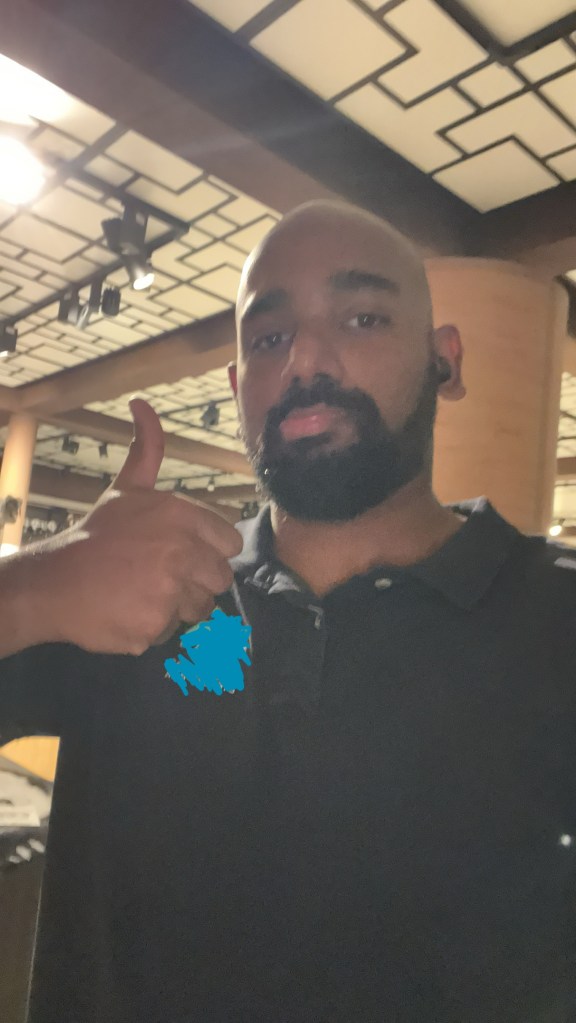

Jack-of-all-part-time-minimum-wage-trades at your service I learned to reframe everything. Work was no longer work — it was cardio and they were paying me to do it. Unknown emergencies were opportunities to prove myself to others, and more importantly to prove to myself that I had what was necessary to adapt. Colleagues were no longer divided into people who could be either kind or unhelpful, but from whom you could always learn something.

I remember one week in stark detail. It began with a waitering role for an apparent charity event by some of the most influential and wealthy people in the Netherlands. As I served the food and took it out, I saw it all: wasted wine and gourmet cuts of beef, someone burning about 20,000 euros for a bottle of perfume, and even a man wearing a pair of tacky shoes leathered with parts of gold — Money can’t buy you happiness, but you’d at least expect it to buy you taste. This was another world to which I had never imagined I could be privy. It was a world where people burned money just to outburn the other and where people threw away wine at 8 euros a glass, because they could taste better in Tuscany tomorrow if they wished. It was later in the week, when I walked into the factory job early one morning and met my team, that I realised the sharp differences of fortune and ability in life.

Here were men from as different a world. A truer world. They were roughly eighty-percent migrants who had done the impossible. They had survived war, the seas and discrimination and settled in an economy that might not have wanted them, but certainly needed them to churn out food for their consumption. A Somalian colleague, a kind man who always helped me when he saw me struggling on the production line once shared his story with me. “My children are my gift. They are all in London!” He yelled over the soulless groans and whizzes of the machinery. “Two of my children are lawyers in London, and the third is a doctor in Queen Elizabeth Hospital.” Working with another colleague, a Bosnian about my age, I learned to enjoy the long repetitive hours. He would always drum on the trolleys at the start of each hour and bellow mock-lyrics to the English music he couldn’t understand playing on the factory speakers. “YooooooOOOOoooo,” He sang to Kings of Leon while operating the machinery, “Your sex is a tyreeeeeeee!”.

Between Mr Tacky-gold-shoes and my factory colleagues, I knew who I’d rather take life advice from; whom I’d rather share a beer or normal-priced glass of wine; from whom I could learn the most about life’s realities and opportunities. Seeing other migrants who had defied all odds sparked something in me. They were the inspiration I needed to succeed. Every lesson I could learn from them, I learned it.

It was somewhere here, when I had just begun to realise that lessons existed in any hardship, that life hurled its last test at me. It was Christmas season when the call came. It wasn’t a Christmas wish or some positive message about the New Year, but the stabbing news of a death. Pilot, my childhood dog and one of my oldest friends had died. I remember I got off my chair as I listened to the news between my parents’ tears, lay on the floor and wept. Then, when I finished weeping, I went to work.

It was afterward at my janitorial job as I ran a Christmas shift alone at night that resilience finally found me. All around me scores of people ran in and out of the toilet, enjoying Christmas, oblivious to the fact that cleaning up after them was a double-mastered janitor with three years of global experience in international development on the verge of shattering. I opened a toilet stall and found that it was in fact possible for a grown adult to miss the target. I also found that in spite of their scattered bombing run, the thought of flushing was beneath them. I held my breath. Held my tears. Gloved up and began scooping shit off the floor and into the toilet bowl. As I knelt as close I dared, scrubbing the toilet seat, I stared at the floaters before me. This was life. More importantly, this was my life: a shitty spectacle that I didn’t plan for. It was full of death, disappointment and kicks in the gut, no matter how much I prepared for it.

It was then that resilience found me. Almost immediately, like a whisper over the shoulder, it reminded me of everything I had learned in the past months. There was no shortage of things for which to be grateful: just as there was direction in disappointment and trial, in death was hidden the celebration and appreciation of a life. Each moment of suffering conceals something that is to be gained. To be learned. To be taken forward. From not knowing how to waiter, to being able to steward at a tacky-gold shoes event; From learning not just the theory-riddled lessons of student life, but the sharp life lessons of hardwork and migrant adaptability — From eighteen euros to security.

As 2025 dawned, I approached the year with a strange new understanding and acceptance. If this was to be my life, I was okay with it. I would learn, and I would adapt, and I would make damned sure that I would work hard while doing it. It wasn’t a week later into January that I got a call on my phone. It was an Embassy in the Hague, and they wanted me for an interview. All my life all I have ever needed was one shot. One chance to prove myself — and I got it.

As I began to leave my many part-time jobs, one of the colleagues from whom I had learned so much assured me that a world of success was in store for me. I can only hope he was right. But right now, each success I have had at my new job at the Embassy in the Hague has been built on the resilience I developed over the months from the factory, to the late night waitering, to my knees on the toilet floor.

A new job in a new city Late nights? No problem. Unexpected strategic communication press release? Sure beats scrubbing shit. Urgent business development facilitation for trade and investment? What a privilege to be excited for work.

In short, I know how to get things done, and I know how to learn to get it done, when I don’t.

My mother used to tell me the only thing you were guaranteed in life was a headache: and hardship is the mother-of-all headaches. As I blaze down the rally race that is 2025, I have no doubt resilience will come knocking again. I’m eager to know what new lessons I would have learned when it does. Just this time I’ll try my damndest to make sure it doesn’t find me in a toilet.

-

Taking the Time: A reflection on my internship in Namibia

Elephants gather at a borehole under a gathering storm “In Namibia you must take time.” Says Johannes. It hasn’t even been a week since I left the autumnal nip of Wageningen for the arid landscape of Tsumkwe, but I have somehow found myself chatting with two travelling electricians over a few shots of Jägermeister. Under a star speckled night sky a herd of elephants drifts to the nearby borehole while we watch.

“My friend, time is everything,” Johannes continues. “When you marvel at these elephants you think it is their tusks you appreciate. But you are connecting to the time it takes to grow what makes each elephant beautiful and unique.” These half-drunk musings hide wisdom beyond the theories of the classroom, and it suddenly strikes me that my internship in Tsumkwe, Namibiamarks the start of a complete and rounded education.

Tsumkwe would never make the list for top ten Namibian experiences. It is a harsh and poorly connected landscape not without its own complications in development. Yet, here I am, driven by my belief that community-driven indigenous aspirations of development can spur meaningful perspectives necessary to decolonise a field with a troubled history of “intervention” and “progress.”

Even with two years of prior experience under my belt, my internship in Tsumkwe with indigenous-entrepreneur Leon Tsamkgao is a masterclass in international development. It affords me the opportunity to bridge the lessons of my classroom at Wageningen with the shifting ground realities of what the development practitioners of yesteryear would carelessly label as ‘the field’.

Working in collaboration with Leon, I learn more about what development aspirations indigenous groups such as the Ju/’hoansi desire. More importantly, I have begun to understand what unique perspectives a single indigenous group can contribute to the field of international development. From a largely peaceful coexistence with wildlife to a profitable indigenous conservancy quickly finding its pace under the disputed promises of community-based-natural-resource-management, there is an abundance of lessons to learn.

A N!oresi in Tsumkwe Yet, these lessons aren’t always sweet. I have also learned that addiction, alcoholism, displacement, and a loss of traditional knowledge run hand-in-hand with other ill-informed notions of development thrust by careless parties under the yoke of “modernisation”. These are challenges I might have learned in the classroom, but never could have understood fully until my placement in Tsumkwe. Nevertheless, these are the troubling juxtapositions a complicated field like development studies involves. As I grapple with my own positionality in this dynamic and charged place, I am reminded that this is why development studies matters; this is why an internship here is so pivotal.

However, the depth of what my internship in Namibia continues to offer me extends far beyond the sharp confines of academia, critical reflection and career progression. Far from Europe and the fast-paced impermanence of Zygmunt Bauman’s liquid modernity, I spend my time in Tsumkwe with a surplus of Johannes the Electrician’s coveted ‘time’.

Here there is time to reflect. Time to talk. Time to meet new and engaging people. I am told that “only interesting people pass Tsumkwe,” and this I believe to be true. I have met no shortage of fascinating faces. I have chatted with archaeologists, engineers, indigenous animal trackers, healers and even a champion World Cup rugby player. I have found the ground to peaceably converse with victims of addiction, apartheid-apologists, and right-wing evangelists. Each conversation leaves an indelible impression on my growth and roundedness as a human being — And perhaps successful “development” requires fewer policy makers and more human beings. Less theory and more empathy.

Driving away from the pans Namibia is not without its challenges. At times it is a struggle. At times I yearn for the comfort of Sri Lankan familiarity. Yet at all times I am aware that my internship in Namibia marks the beginning of a new and exciting chapter in my life. Like all good stories it will have its share of challenges and breakthroughs. Victories and failures. Denouement and character-arcs as novelists would put it.

I never met Johannes the Electrician again. I probably never will. But the wisdom of his half-drunk musings rings true. My internship in Tsumkwe is much more to me than simply learning international development à là “the hands-on approach”. It is a union of classroom theory with the everyday lived experiences of Tsumkwe. The culmination of lectures and prior career experience with a dynamic place where community-led indigenous development is taking the fore. It is the sum total of the wisdom in all the exchanges I have with the interesting people with whom I cross paths.

It is holistic. It is time.

The above reflection was a piece I wrote to Wageningen University & Research for the chair-group Sociology of Development & Change during my MSc International Development Studies internship component

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.